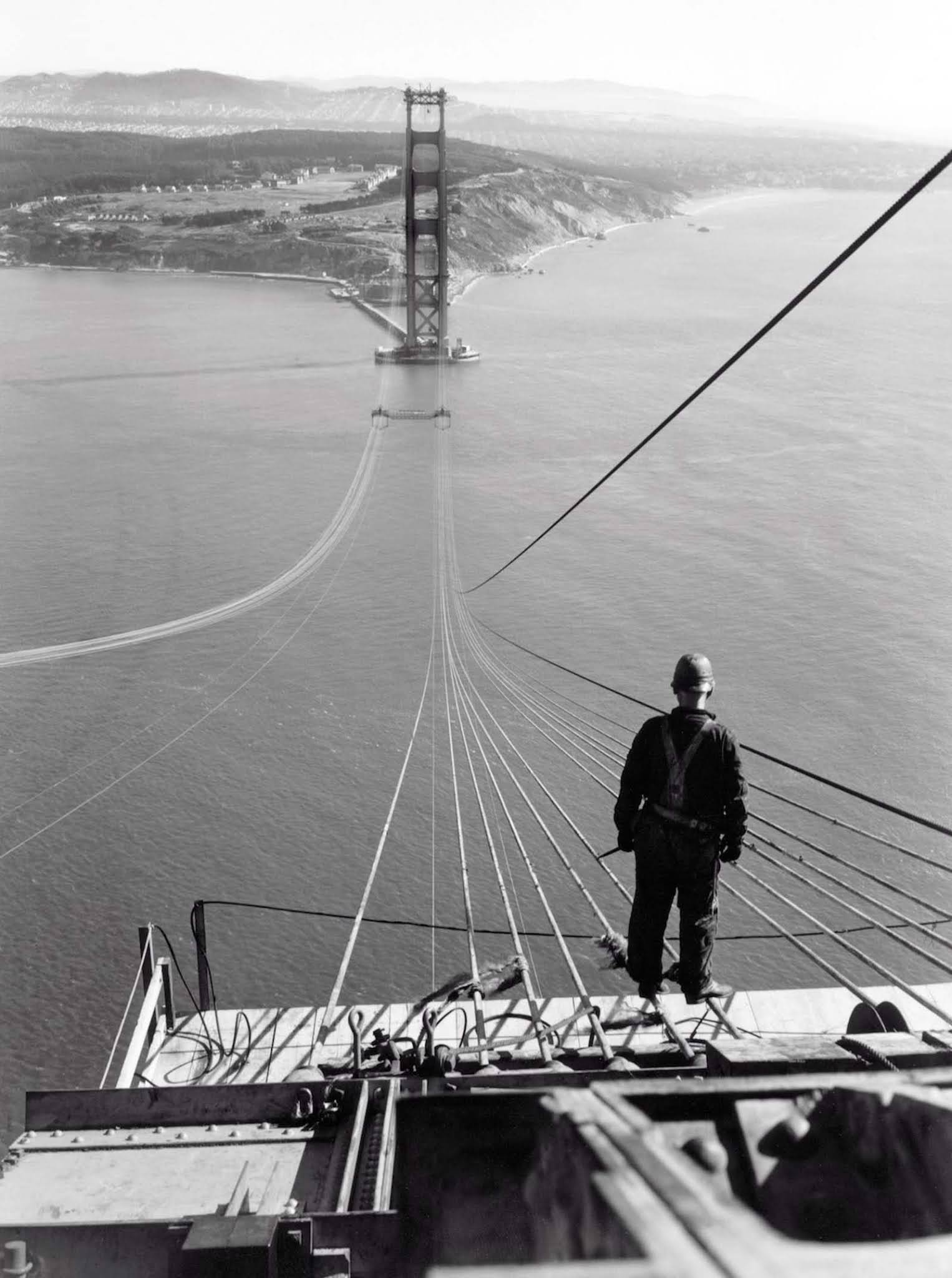

A man standing on the first cables during the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, with the Presidio and San Francisco in the background. 1935.

The Golden Gate Bridge is unquestionably an American icon whose symbolism power rivals that of the Empire State Building and Statue of Liberty, in part through its representation of optimism, a distinctly American trait.

Its visual linkage of form and nature, purpose and design, does not mark a boundary but instead symbolizes Western opportunities and Pacific possibilities. Here the American values of hope, possibility, and success mix with the future, represented by the ocean extending beyond the bridge itself.

The Pacific Ocean brings fierce storms, rough waters, and high winds into the Golden Gate. Additionally, the area is an earthquake zone. By the early 1900s, scientists had determined that rigid bridges could fracture and collapse in such conditions.

Joseph Strauss and his two engineering consultants, Charles Ellis and Leon Moisseiff, determined that a suspension bridge would be the best fit for the Golden Gate.

In the 1930s, when work began on the Golden Gate Bridge, suspension bridges were becoming more common. In earlier bridge designs, the main supports were normally beneath the roadway, holding it up.

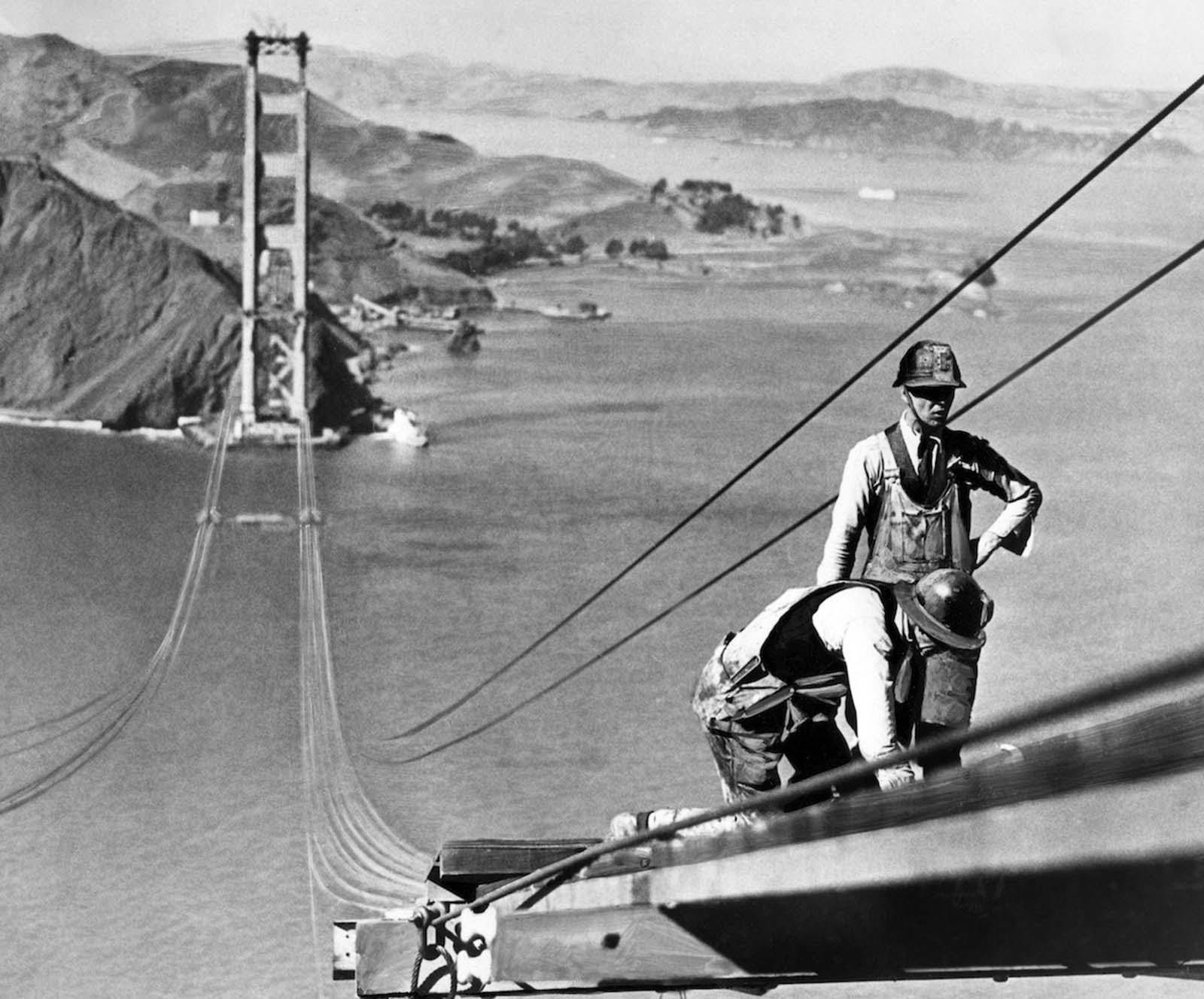

The roadway in a suspension bridge is suspended or hung, from strong wire cables. The cables are flexible, allowing the bridge to expand and contract in hot and cold weather and to swing in high winds without breaking.

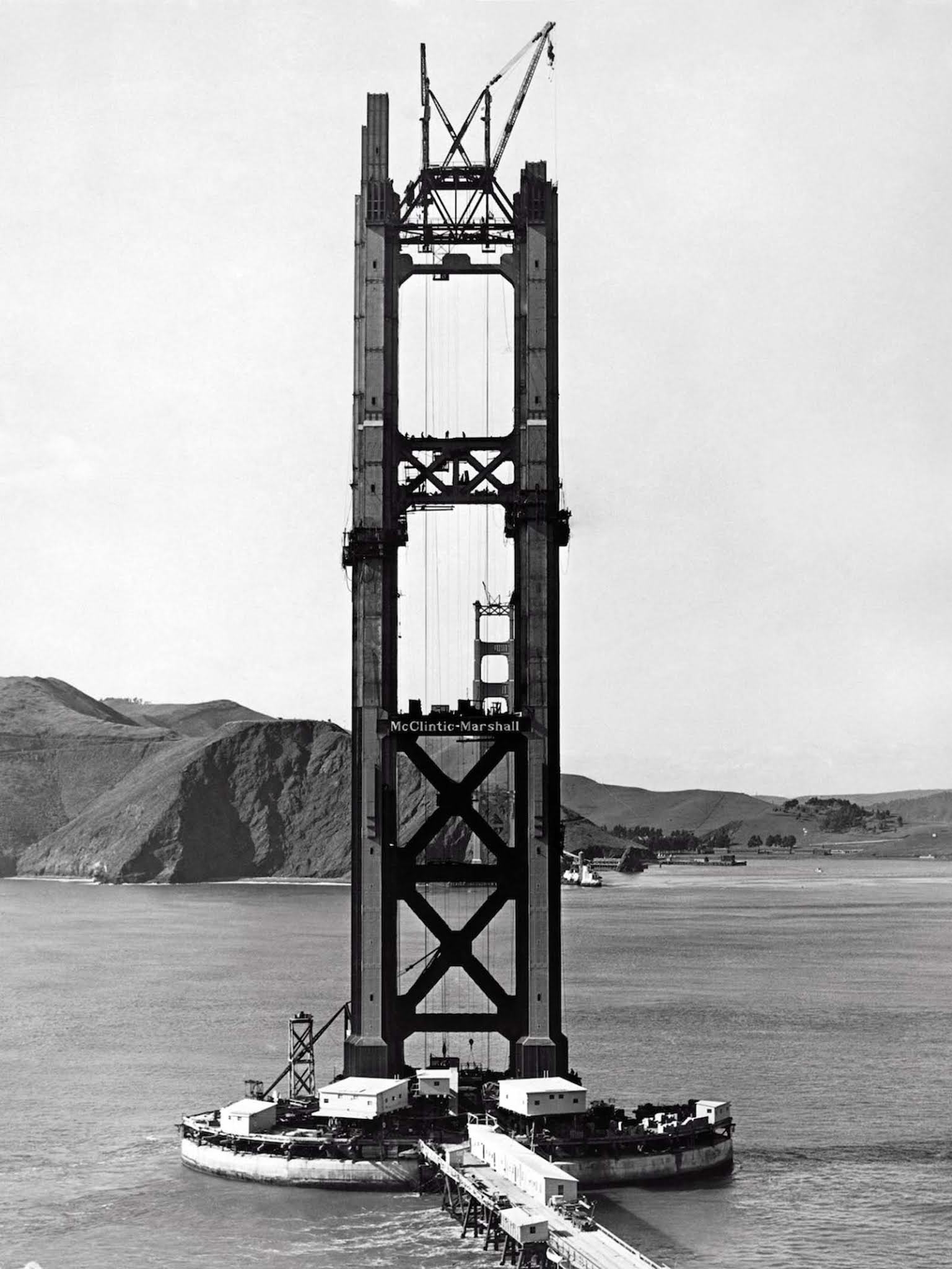

A freighter heads out to sea past the lone sentinel of the Marin Tower. 1934.

The project got underway in January 1933 as workers dynamited rocks and dug pits for the bridge’s anchorages. The anchorages, made of thick cement, hold the ends of the giant cables at opposite shores, “anchoring” the bridge to the ground. Finished a month later, the first task was quite simple compared to the monumental steps that lay ahead.

The Golden Gate Bridge broke new ground in the history of bridge design. Never before had a bridge been attempted at an ocean entrance, and the building project was dangerous, expensive, and time-consuming. Workers easily constructed the concrete north pier, the cement pillar on which the north tower would rest, by June 1933.

The south pier, however, was to be built 100 feet (30.5 m) below the surface waters of the rough Pacific Ocean. This required the work of divers and the construction of a huge protective concrete barrier, called a fender, around the pier. The south pier took nearly a year and a half to complete.

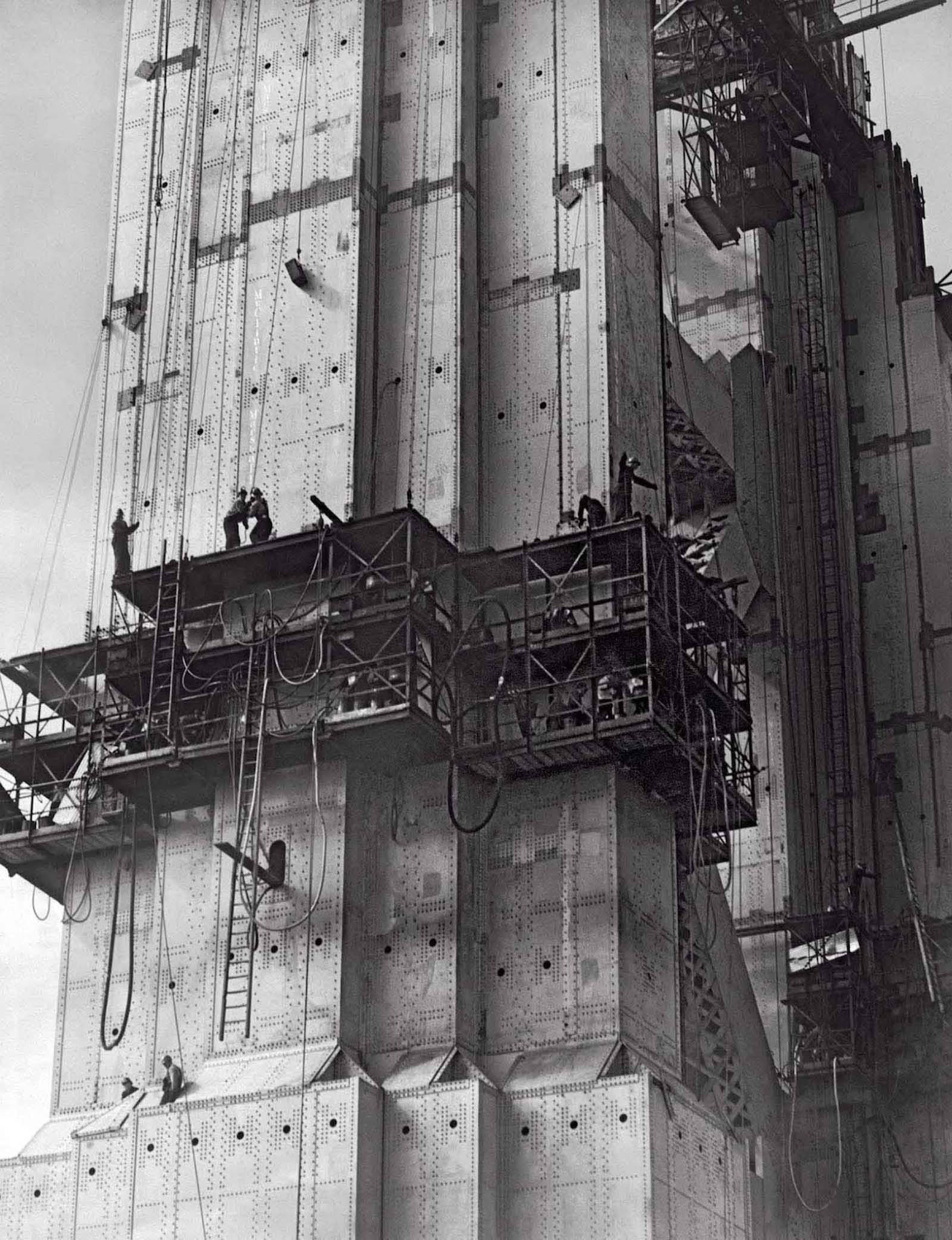

Meanwhile, the two towers of the bridge, supported by the piers, were constructed out of preformed steel pieces. For two years, workers riveted the steel pieces together from the piers upward, until the structures reached into the sky. The workers and their foramen took increased precautions as they climbed higher.

Hard hats were required for all jobs, and a huge safety net was strung beneath the bridge. At that time in bridge construction, one life was typically lost for every $1 million spent. While 10 workers lost their lives in the falls from the Golden Gate Bridge’s wet, slippery steel, the net saved 19 others.

Riveters at work in cages on the South Tower.

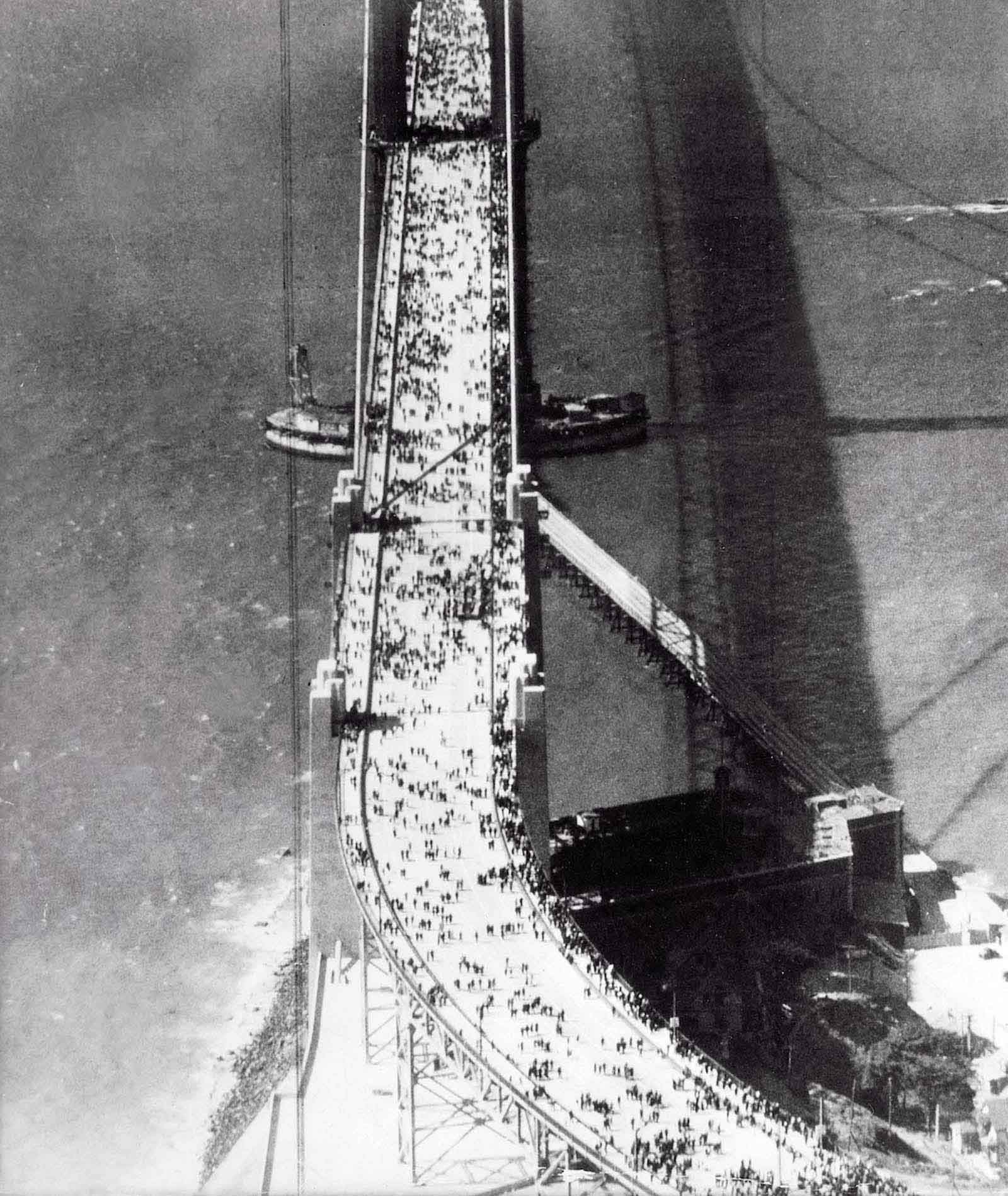

Since its opening, the bridge has been thoroughly used and admired. Eighteen hundred cars and 2,100 pedestrians crossed in the first hour of its operation, and by midnight of opening day, an estimated 25,000 cars and 19,350 pedestrians had paid their tolls (fifty cents per car, five cents per pedestrian). By the end of its first fiscal year, 3,326,521 vehicles had crossed. By the end of 1970, the annual number was 33 million.

With such numbers, it is no surprise that the bridge was paid for (the cost was 35 million dollars) by July 1971. And it is no surprise that in 1994, the American Society of Civil Engineers designated the bridge as one of the seven wonders of the United States, this for a bridge designed in Chicago, fabricated in Pennsylvania, and shipped through the Panama Canal.

The bridge’s popularity and frame are balanced by its constant upkeep. Because it stands just 12 miles east of the San Andreas fault and severe weather is a continual threat, the need to upgrade and retrofit the bridge is acute.

Remarkably, the bridge already has withstood high winds, storms, and earthquakes such as the devastating Loma Prieta quake of 1989.

The bridge deck’s ability to move 7 feet in either direction vertically or 12 feet horizontally is one secret. Another is that the bridge is composed of six elements (approaches, piers, towers, roadway, center span, and cables), not just one so that each moves individually. But uniting all these factors is the bridge’s artful merging with nature, maintaining its integrity without sacrificing beauty.

A worker running up one of the catwalks being built for the construction of the cable. 1935.

View of the South Tower. 1935.

Two workers straddle the bridge cables. 1935.

A view of a bridge tower. 1935.

Setting roadbed sections in the fog. 1936.

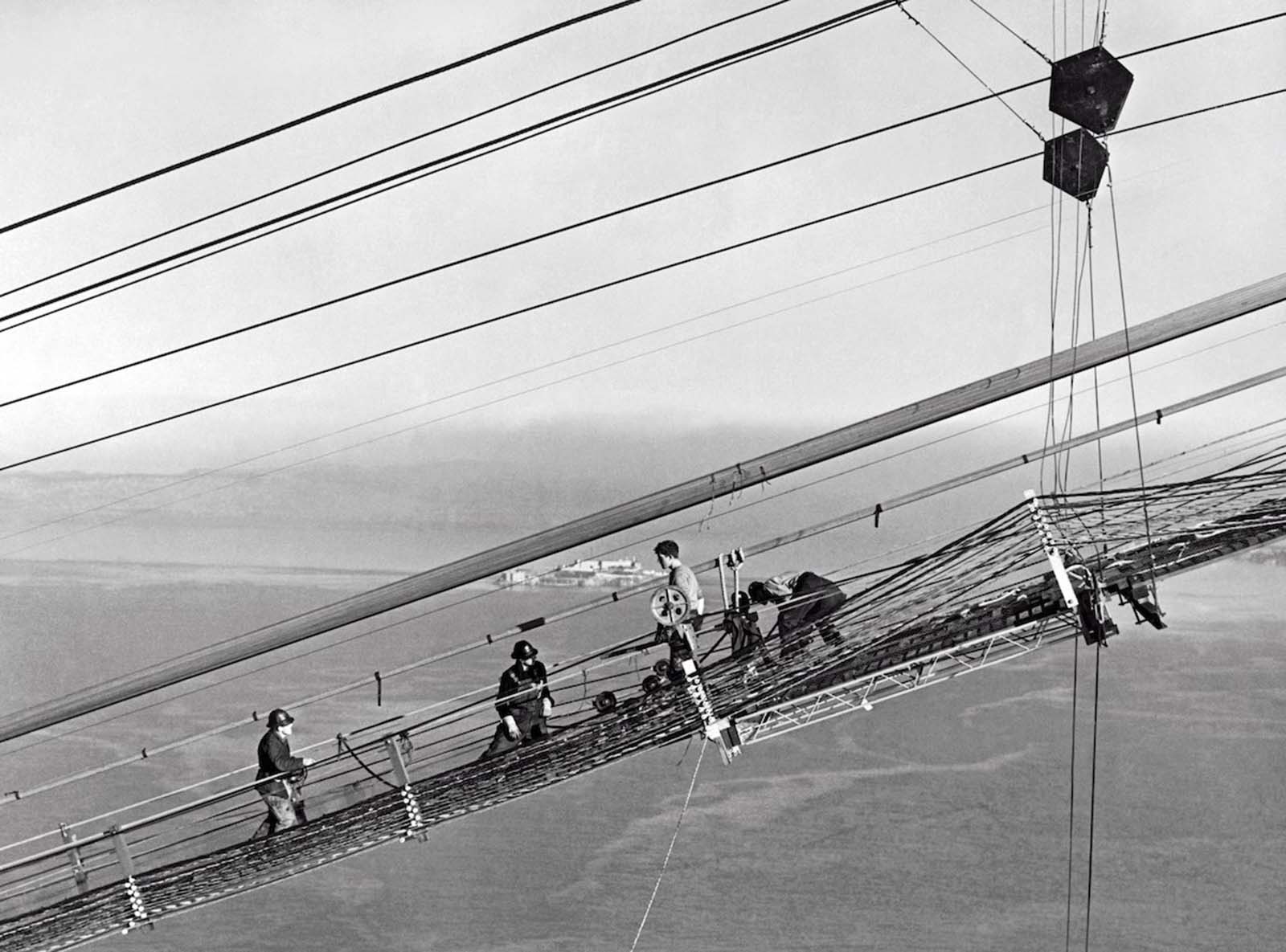

Workers on the catwalks bundling the cables during the construction of the cables. 1936.

Men on the catwalks working on the cables. 1937.

Tourists view the bridge being built from a boat. 1936.

A workman walks on the levee that connects Fort Point to the south tower. 1936.

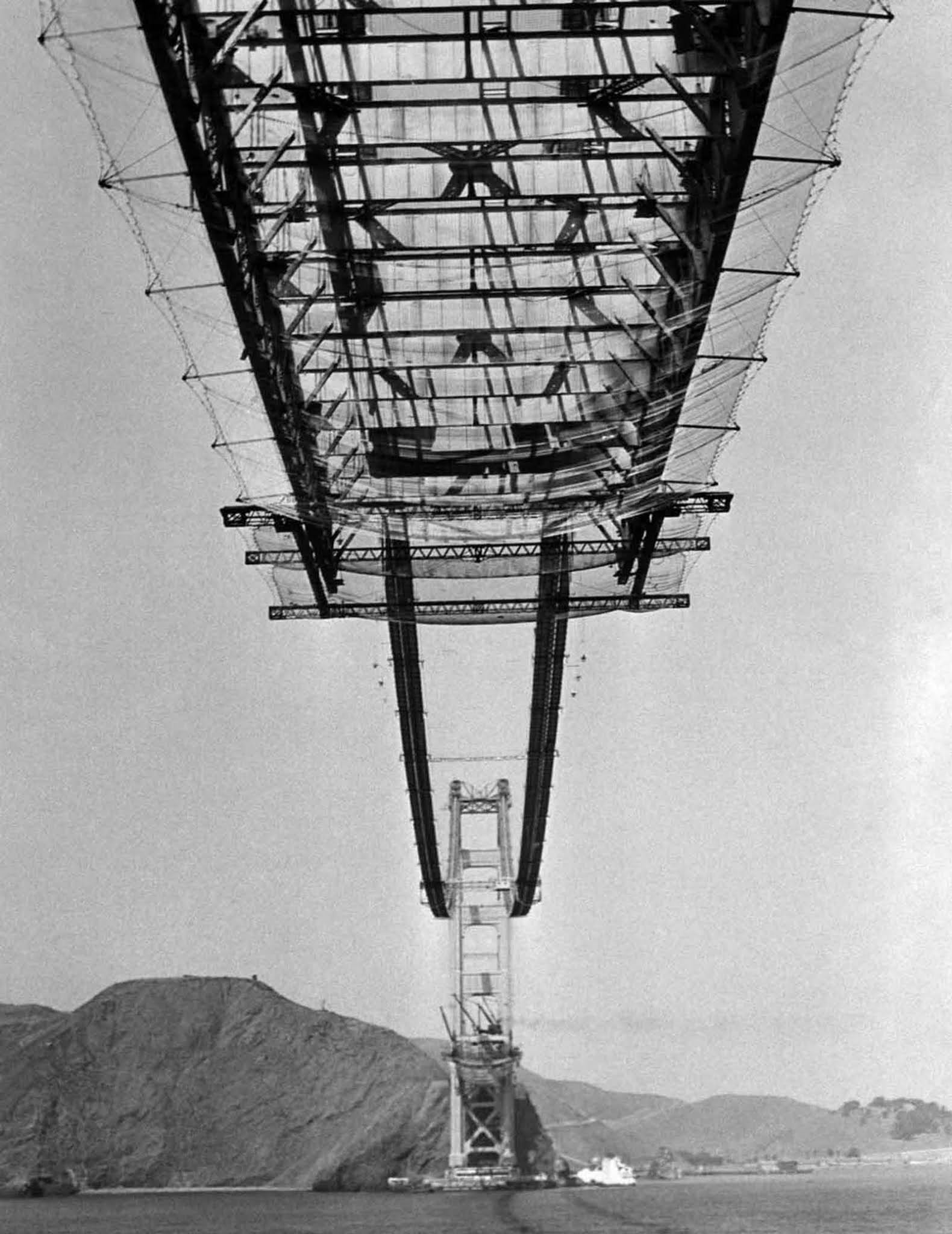

Reaching outward from each side of the Golden Gate, a huge safety net stretches from shore to shore to protect the lives of workers on the Bridge.

View of the Marin Tower.

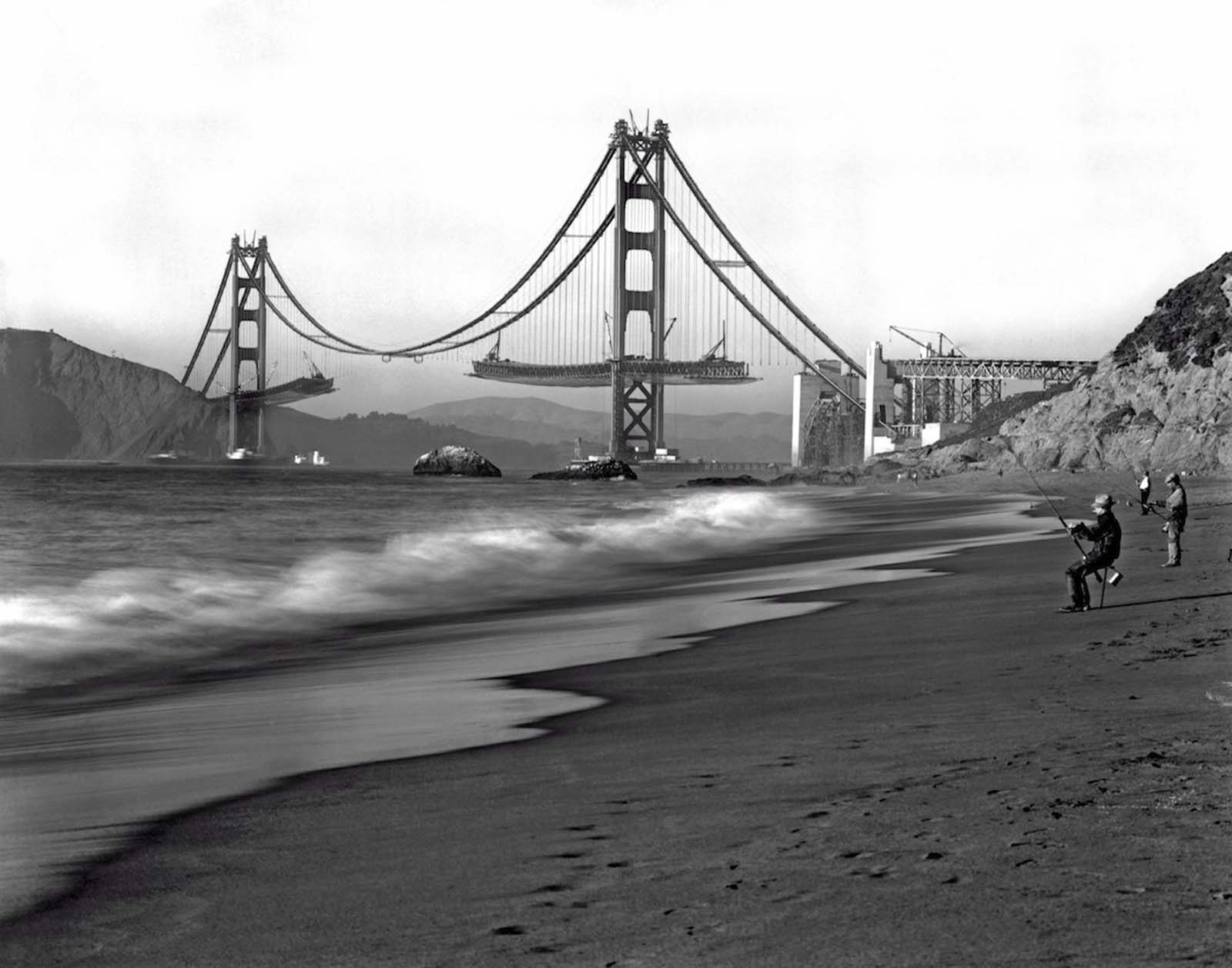

Fishermen on Baker Beach. 1936.

A U.S. Navy battleship cruises under the cables of the bridge as it is being built. 1936.

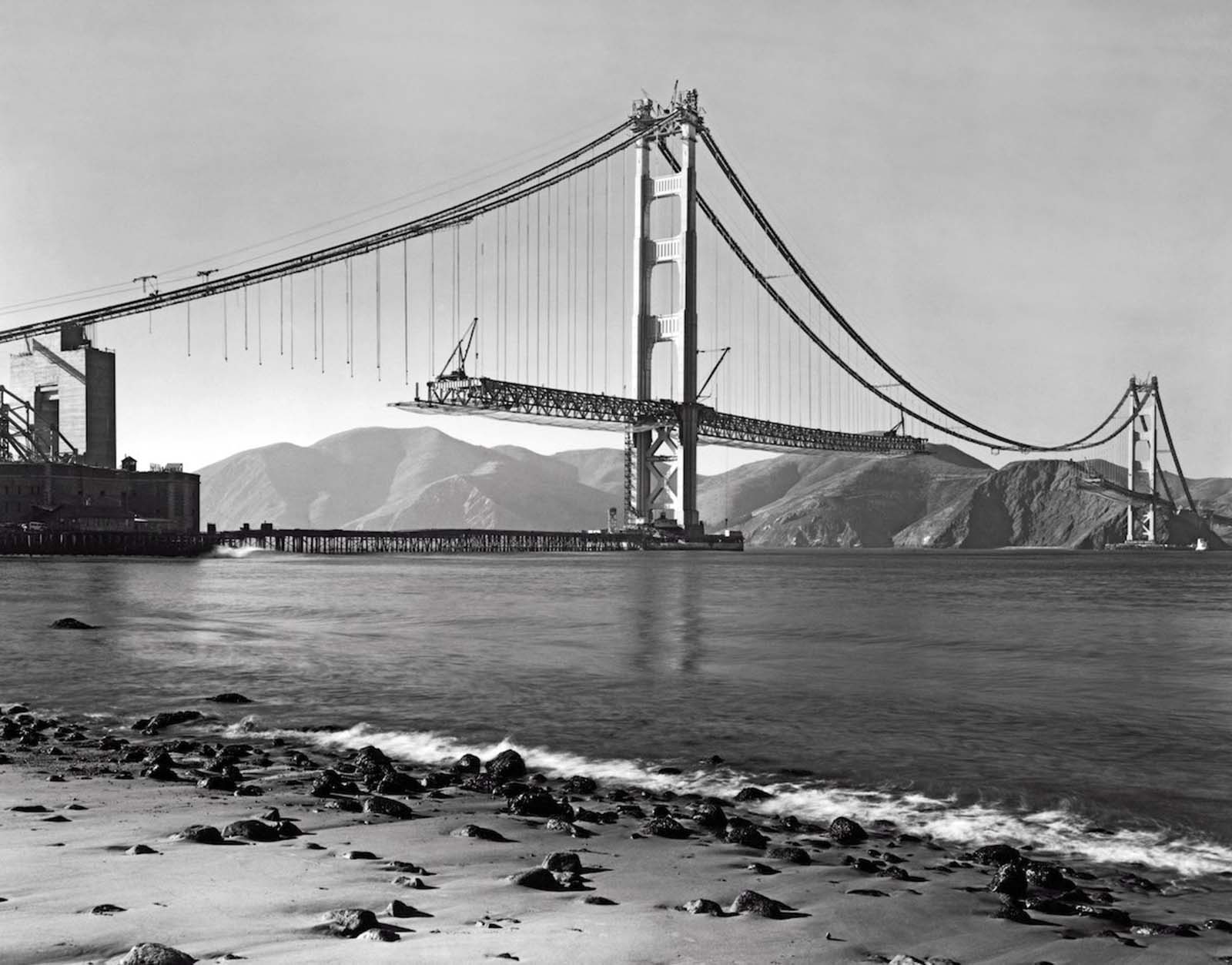

View from Crissy Field in the Presidio, with the roadbed being installed. 1937.

Opening of the bridge to pedestrians. 1937.

The inaugural drive across the bridge. 1937.

The opening of the bridge to traffic. June 8, 1937.